Well defined semantics for positions and displacements.

The Affine Space

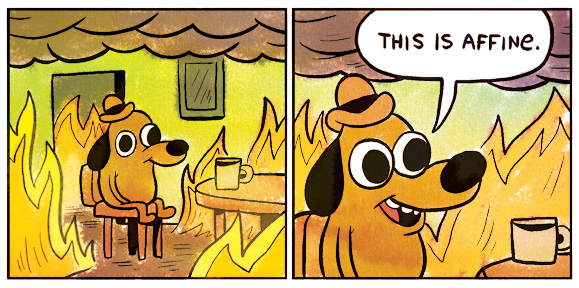

I recently came across a geometric structure that deserves to be better known: The Affine Space.

In fact, like many abstract mathematical concepts, it is so fundamental that we are all subconsciously familiar with it though may have never considered its mathematical underpinnings.

Strangely enough, once I assimilated the concept, my Baader-Meinhof phenomenon kicked in and it seemed that everyone is suddenly talking about the Affine Space. I’ll be linking to multiple resources that do a much better job than I can at explaining them.

This post will introduce the Affine Space structure and focus mainly on its role in the C++ type system, the standard library and for creating new strong types.

CAVEAT EMPTOR

This post is not about other common “affine” topics such as:

- Affine Transformations: In computer graphics and image processing, geometric affine transformations are parametric shape deformations where parallel lines (in e.g. 2D or 3D) remain parallel after the transformation;

- Affine Type Systems: I really wanted to title this post Affine Types, however in Type-Theory affine type systems are well defined.

Although these may be indirectly and mathematically related, any such link is beyond the scope of this post. Similarly, I will not delve into many of the deeper mathematical aspects, details and connections.

My focus (and perhaps the main reason you may find this post interesting and different from other resources) will be on the formalization and its role in better API design and more specifically the design and public interface of classes or class templates.

WARNING: I am not a mathematician. The explanations, intuitions and interpretations are my own and thus may be utterly wrong. If you find such errors, please drop me a line in the comments (or elsewhere) so I can be enlightened and correct the mistakes.

I am writing this as a programmer to a programmer, so although familiarity with elementary-school Linear Algebra is assumed, that you are a mathematician is not.

Also, I am treading a fine line between mathematical purity and pragmatic C++, so even where not explicitly stated assume an asterisk reasonably ignoring edge-cases with undefined-behaviors.

Motivating Examples

Pointer Arithmetic

Consider the following C code:

typedef float T; // declare T

T arr[42]; // an array of T

T* beg = &arr[0]; // pointer to first element of the array

T* end = beg + 42; // pointer to one past the end of the array (OK, not UB)

int cnt = end - beg; // element count or offset

T* last = beg + cnt - 1; // pointer to the last element

int neg = beg - end; // a negative or backwards offset from 'end'

There are four types in use in this snippet:

T(float)T[42]T*int.

T is arbitrarily chosen here as float and T[42] is not really relevant to this example (it is here to avoid UB).

We are interested in the interactions of the two remaining separate types: int a signed integer and T* a pointer.

Observe that:

- We can add integers to pointers and subtract integers from pointers [1].

The result is a pointer type. - We can also subtract pointers to get a (signed) integer type [2].

- Integers can (obviously) also be added, subtracted and multiplied by each other to get other integers (closure under addition and multiplication [3]).

Note however, that mathematically for integers subtraction is not really a standalone operation (operator) but really just a notational shorthand (or syntactic sugar) for addition with the inverse (the right-hand-side multiplied by-1).

However, this code does not compile:

beg + end; // Error C2110: '+': cannot add two pointers

42 - beg; // Error C2113: '-': pointer can only be subtracted from another pointer

beg * 3; // Error C2296: '*': illegal, left operand has type 'T *'

MSVC’s errors are very informative here and teach us that the addition, subtraction and multiplication operations are only allowed for some type combinations and, as in this case, not for others.

What does adding two addresses mean? What does it mean to multiply an address by a scalar (negative or otherwise)? These questions do not have a clear answer (or any answer for that matter) and thus these operations are not permitted.

Given “meaning” == “valid semantics”;

We desire: “no meaning” == “invalid semantics” and;

“invalid semantics” ⇒ invalid or rejected syntax.

The value of a pointer is just a number, an integer, an index, specifying the “cell-address” offset in some memory address space. So does this mean that T* x and using *x are just syntactic sugar in C for some base_addr[x]?

No. Even in C, and most likely even in earlier languages, there is a semantic distinction of types that does not allow pointers to behave as regular (indexing) integers.

In other words, a pointer is an integral value (typically unsigned) with non-arithmetic semantics (and hence a special syntax).

In C++ (as in C) the correct integer type to use for pointer arithmetic in not int but is an implementation-defined standard type called std::ptrdiff_t (which may or may not be an int).

The final observations are about commutativity:

- Addition is commutative, so both

beg + 1and1 + begare identical valid pointers to the second element. - Subtraction is obviously not commutative, so while

end - 1is a valid pointer to the last element,1 - endis meaningless and will not compile.

Again, the compiler is enforcing the special semantics.

Pop Quiz:

- Given two integers

aandb, find the mid-pointm(up to truncation). - Given two pointers into an array

aandb, find the element in the middlem(up to truncation). - Is the simplest code identical? If not why not?

- BONUS: Could (2) be hypothetically solved with just one additive operation and one multiplication, while maintaining pointer semantics?

👇

Iterators

Iterators are a generalization and abstraction of pointers. With a few minor tweaks:

typedef float T; // declare T

std::vector<T> vec = {0,1,2,3}; // a vector of Ts

auto beg = vec.begin(); // iterator to first element in the vector

auto end = vec.end(); // end iterator

int cnt = end - beg; // element count or offset

auto last = beg + cnt - 1; // iterator to the last element

int neg = beg - end; // a negative or backwards offset from 'end'

The code is essentially the same. Again we see the interaction between the iterator type std::vector<T>::iterator and an offsetting integer. In this case the correct integral type to use would actually be std::vector<T>::iterator::difference_type.

This code works because std::vector<> iterators are RandomAccessIterators and thus support the + and - operators as used here.

Of course, beg + end, 42 - beg and beg * 3 are still invalid expressions and do not compile.

Non-RandomAccessIterator iterators do not support these operators, but we may still achieve something similar:

typedef float T; // declare T

std::set<T> set={0,1,2,3}; // an set of Ts

auto beg = set.begin(); // iterator to first element in the set

auto end = set.end(); // end iterator

auto cnt = std::distance(beg, end); // element count or offset

auto last = beg; // copy 'beg' into `last`

std::advance(last,cnt - 1); // increment 'last' to the last element

auto neg = std::distance(end, beg); // a negative or backwards offset from 'end'

The function std::distance() functions as the offset finding subtraction operator and using it is only syntactically different. Conversely, although std::advance() functions like the integer offseting operator +, its API and semantics are different, since it mutates its input argument and returns void. I guess it is more akin the sematics of the += operator (more on mutation later). So we must initilize last with two (non-composable) steps.

We may be seeing here an API design decision that may not have fully considered iterators and their operators in the Affine Space context… [4]

👍

Post-posting Update: As Ed C points out in the comments below, the standard library function std::next() (and std::prev() too) in fact is equivalent to the integer-offseting operator + and has the same semantics (it only defaults in incrementing by 1):

typedef float T; // declare T

std::set<T> set={0,1,2,3}; // an set of Ts

auto beg = set.begin(); // iterator to first element in the set

auto end = set.end(); // end iterator

auto cnt = std::distance(beg, end); // element count or offset

auto last = std::next(beg,cnt - 1); // iterator to the last element

auto neg = std::distance(end, beg); // a negative or backwards offset from 'end'

⌚

<chrono> Types

But enough with pointer-like examples. Consider the following code:

using namespace std::chrono;

auto beg = system_clock::now(); // start time

// ... do something worthwhile

auto end = system_clock::now(); // end time

auto dur = end - beg; // total duration

auto almost = beg + dur - 1ms; // just before end

auto next = beg + 2*dur; // time when taking twice as long

auto ago = beg - end; // a negative or backwards time offset from 'end'

The C++11 <chrono> library is the standard way to measure time (in C++20 it will also portably handle dates). At its heart, <chrono> distinguishes between two distinct types:

std::chrono::time_point<>- a point in timestd::chrono::duration<>- a time interval

In the snippet above, beg, end, almost, next and ago are all time_points.

The variables dur, 2*dur and the literal 1ms are durations.

As expected, beg + end, 42ms - beg and beg * 3 are again invalid expressions and do not compile.

This is no coincidence. Howard Hinnant the original chrono designer was well aware of Affine Space semantics.

Are you seeing the pattern yet?

🚀

Up to now all the types we’ve seen have been one dimensional types like indexes, addresses and points along the time line. But as its name implies, Affine Space semantics also extend to higher dimensions.

Motivating Counter-Examples

Point Arithmetic

As you may have surmised by now, what all these examples have in common is the concept of a type representing a location, a point or a position and a second associated type representing a displacement (shift, offset, duration). These concepts naturally generalize to higher dimensions.

Consider this innocuous OpenCV code snippet:

// Vector math is fine

cv::Vec2i jump = { 0,42 }; // a 2D vector: up

cv::Vec2i step = { 42,0 }; // a 2D vector: right

cv::Vec2i jump_fwd = jump + step; // the jump direction (vector addition)

cv::Vec2i run = 2 * step; // faster motion (vector scaling)

cv::Vec2i bump = -step; // inverted direction (vector scaling)

// ...

In higher dimensions, vectors take the role of the scalars for the displacements (shift, offsets) that we saw previously. Vector math is well defined in linear algebra and all is well. (cv::Vec2i is a 2D vector with integer elements.)

We continue:

cv::Point pos = { 0,0 };

cv::Point next_pos = pos + cv::Point{step}; // WAT?

cv::Point dir = next_pos - pos; // Umm..

cv::Point huh = -pos; // Huh?

cv::Point hmm = pos * 2; // Hmmm...

At first glance it would appear that the cv::Point type represents a 2D point. However, not only does it not easily interact with the cv::Vec2i type (requiring an explicit cast), in fact, it supports all the same arithmetic operations as the vector type. It does not expose the semantics of a “true” point type where “invalid semantics” ⇒ invalid or rejected syntax.

This type of API may be convenient, but as the Mars Climate Orbiter developers learned so is storing thruster force in “pounds of force” and/or “newtons” as bare untyped numbers.

Not to pick only on OpenCV, the Eigen C++ template library for linear algebra, provides only vectors and ignores the concept of points althogether.

Easy Quiz: Given N cv::Points, find their centroid (center-of-gravity).

🤘

Post-posting Update: Slack user @pgbarletta points out that CGAL (The Computational Geometry Algorithms Library) does get these semantics right!

☁️

Aloof Points

My last counter-example is from PCL, The Point Cloud Library. Surely a C++ library dedicated to manipulating points would provide points with meaningful semantics.

Sadly this is not the case:

pcl::PointXYZ origin = {0,0,0};

origin.x += 1;

origin.y += 2;

origin.z += 42;

The only meaningful operations one can perform on points, is member access. This causes code using PCL point types to be very verbose and error prone. There isn’t even a vector type in PCL. When needed, the Eigen vector types are used (though there are no semantic relations and operators between the types).

When someone asked about this API omission, the reply was:

“Why would they ? what is the meaning for ,e.g., the + operator? this is not defined mathematically.”

This is technically correct for the + operator but as we’ve seen, definietly a cop-out with regards to point subtraction and displacement types.

🔥

The Affine Space

Definition

Intuitively:

- A point is a position specified with coordinate values (e.g. location, address etc.).

- A vector is specified as the difference between two points (e.g. shift, offset, displacement, duration etc.).

If an origin is specified, then a point can be represented by a vector from the origin, however, a point is still not a vector in coordinate-free concepts.

There are many mathematical definitions of an affine space, such as “a vector space that has forgotten its origin”. Here’s one with minimal math jargon:

- An affine space has two types of entities (i.e. types): points and vectors.

- All the vectors form a vector space:

- Closure under the usual two operations:

- Addition of vectors

- Multiplication by a scalar.

- Vector subtraction and negation is “syntactic sugar” for addition with the right-hand-side multiplied by -1.

- A Linear Combination of vectors is also a vector and is the weighted sum of one of more vectors.

- Closure under the usual two operations:

- An affine space has the following properties:

- There is a unique vector v related to a pair of points p and q, defining two operations:

- Subtract two points to get a vector: p-q=v

- Add a vector to a point to get another point: p+v=q

- An Affine Combination of points into another point is a weighted sum of one of more points when the total sum of the weights is exactly 1.

- An Affine Combination of points into a vector is a weighted sum of one of more points when the total sum of the weights is exactly 0.

- A weighted sum of one of more points when the total sum of the weights is neither 1 nor 0 is undefined.

- There is a unique vector v related to a pair of points p and q, defining two operations:

The Affine Combination properties 3.2 and 3.3 are not strictly definitions since they can be directly derived from 3.1 by showing that such a weighted sum can be factored to a sum of vectors (3.3) plus a point (3.2) (single line proof).

IMPORTANT: Note that an affine combination of points is not a general linear combination and is only defined when the weights sum to 0 or 1, and in each case the result is a different type - a vector or a point respectively.

The affine combination weight tuples are called the barycentric coordinates of the points of the space.

Types

We can translate these definitions to types and operator type signatures

(<arg types> -> <return type>):

- An affine space API consists of three inter-related types:

Point,Vector,scalar Vectorclosure consists of:- Addition (infix):

Vector + Vector -> Vector

- Commutative scalar multiplication (infix):

scalar * Vector -> VectorVector * scalar -> Vector

- As syntactic sugar, we can also define (infix) subtraction:

Vector - Vector -> Vector-Vector -> Vector(unary) negation

- Addition (infix):

- We also defined the following operator between

PointandVector:- Find displacement as (infix) point subtraction:

Point - Point -> Vector

- Displace point as (infix) addition:

Point + Vector -> PointPoint - Vector -> Point(syntactic sugar)

- Find displacement as (infix) point subtraction:

The types Point and Vector have the same dimension. They often also share the exact same representation e.g. a tuple of one of more numbers. The numbers are typically (but not always) of the same type as scalar. Of course, Point and Vector may be template classes parameterized by aspects like, element type, precision etc. In <chrono> for example, chrono::duration<> is a family of types and its internal representation generally differs from that of chrono::time_point<>.

If our types are mutable, we can also add the following operators:

Vector *= scalar -> VectorVector += Vector -> VectorVector -= Vector -> VectorPoint += Vector -> PointPoint -= Vector -> Point

We cannot add Point -= Point -> Vector since the return type is a Vector and not the left hand side Point.

Affine Combinations

Spoiler alert: Quiz Solutions Ahead!

Given two integers a and b, the mid-point (up to truncation and ignoring overflow) is m = (a+b)/2.

Given two pointers a and b into an array, the middle-element between them cannot be m = (a+b)/2 since, as we’ve seen, one cannot add pointers. Instead the mathematically equivalent m = a + (b-a)/2 maintains the affine semantics of adding a (scaled) displacement to a position.

We can also notice that mathematically: (a + b)/2 == ½*a + ½*b, and ½ + ½ = 1.

So the mid-point is in fact a case of an affine combination since the weights sum up to 1.

In higher dimension, e.g. given 2D points p,q,r, the center of gravity is the affine combination (p+q+r)/3 (or CoG = ⅓*p + ⅓*q + ⅓*r).

From an API design point of view, the operators defined above are typically straightforward to implement. However, they do not allow one to write (only valid) affine-combinations. One must mathematically decompose the affine combination into the constituent point/vector operations (which, incidentally, is exactly what the affine-combination derivation proof does!).

I had not seen language constructs or libraries or APIs that allow and enforce that the combination weights sum exactly to either 0 or 1. For weights that are known at compile time, one can imagine an expression template decomposition that can validate this at compile-time (and allow Point/scalar multiplication and Point/Point addition operators only for intermediate temporaries). For run-time weights this would have to become a run-time “semantics” test.

If you know of one or come up with such an interface do let me know.

💪

Strong Types

Strong type libraries such as Jonathan Müller’s type_safe, Jonathan Boccara’s NamedType and Björn Fahller’s strong_type allow us to create separate distinct types from the same underling types. Similarly, unit type libraries allow compile time enforcement of unit management.

Affine space semantics, provide another venue for strong type semantic enforcement that is specifically tailored to representing the general concepts of positions and displacements. In fact, when writing a physics or engineering system such as, say, a planetary orbit insertion module, it would make sense to apply both a unit system and affine semantics to catch at compile time problems that might otherwise only be identified at investigating committee time. Both are orthogonal and provide multiple layers of compile time security. In fact, amongst other goodies, this is exactly what chrono provides: a time-point and duration abstration and a generic time units system.

As I was writing this post, the question of Martian time and date representions came up on Slack and how [C++20] <chrono> will handle such unearthly appointments. Howard Hinnant (the chorono designer) commented:

See here, here and here for examples of non-civil calendars that can interact with

<chrono>. Mars could just be another calendar. At the end of the day, all that is required is conversions to and fromsys_time, which is Unix Time.Martian days, hours and minutes could easily be duration aliases in the Martian namespace. The key is to not have a single type represent more than 1 thing. E.g. a Martian year and an Earth year should not both be represented as

std::chrono::year.Choose your precision and choose to truncate it however you like if you choose to truncate at all.

Freely interpreting this: Take your earthly time_point, subtract the Earthly “origin” date (the Unix 00:00:00 (Thursday, 1 January 1970)) to get a “calendar-free” duration. Now add this duration to the Unix time as represented in the chosen Martian date system. The result is a Martian time_point in the chosen calendar.

Subtleties

In the 1D case of pointers, the displacement type is an (implementation defined) signed integer. As primitive integers, they can be multiplied and also use to offset different pointer types.

Offset multiplication is a valid operation only when one of the product elements is considered as the scalar. Displacement-multiplication is undefined in general.

A more interesting case is as follows:

int arr[42]; // an array of ints

int* pint = &arr[0]; // an int*

int* qint = &arr[42]; // another int*

auto diff = qint-pint; // the offset between int "cells"

char str[42]; // an array of chars

char* pchar = &str[0]; // a char*

char* qchar = pchar + diff; // <<== ???

Here the C[++] type system allows us to use the displacement diff between two int* positions to offset a char* position.

Are these semantics valid?

As far as I can tell, that is a domain specific question. There are several cases one may encounter each with potentially different semantics.

In the general case, say with two unrelated arrays or STL containers, e.g. for std::vector<>, the difference type is std::vector<T>::iterator::difference_type and may potentially be dependent on T so such operations would be disallowed and maybe potentially UB for array.

However, in some cases this is not so. Consider using SoA (Struct of Arrays) - a commen technique in gaming where e.g. 3D object vertex XYZ coordinates are stored separately from the texture UV and color RGB values. Although all the arrays are of different types, have exactly the same length. Here there is a strong affinity (see what I did here?) between the arrays and offsetting to the middle vertex means hopping the same number of hops in the texture and color arrays as well. In this case, semantics that allow mixing of types does make sense.

Another case, suggested by Björn Fahller, is the case of an isomorphism between the systems or spaces. For example when plotting a graph. Then it obviously makes sense to translate e.g. durations to centimeters or pixels, but this is an isomorphic translation, where you map from one space to another and and expicit [unit] conversion should be required.

Does

size()Matter?There is a never-really-ending discussion (i.e. disagreement and/or regret) about the type that the

.size()method on standard containers (or views) should return. Should it be signed or unsigned?The standard chose the container

size()methods to returnsize_typewhich is an implementation defined “unsigned integer type” which “can represent any non-negative value ofdifference_type”.cppreference.com claims that : “

size()returns the number of elements in the container, i.e.std::distance(begin(), end()).”.However, the return type of

std::distance()isdifference_typeis “a signed integer type” and “is identical to the difference type ofX::iteratorandX::const_iterator”.

difference_typeis “a type that can be used to identify distance between iterators”. This means that as we’ve seen, in general such a distance must be signed.

However, signed integers can represent only half as many elements as the unsigned type ([standard] containers cannot contain a negative number of elements) and is a type for which overflow in arithmetic is undefined behavior.

So,size()might not, in fact, be implemented as a cast ofstd::distance(begin(), end())since it is specified to be unsigned and may be larger than whatstd::distancecould be able return.There are other subtleties related to overflows, wraparound, unsigned vs. signed arithmetic and undefined behavior. The debate will likely rage on, but is way beyond the scope of this post.

[Reddit readers: please do not latch onto just this sidebar.]

Reification

The concepts I presented here have well defined semantics and should help guide you for better API design for your custom types.

I wish I could point you to a generic library that can take an int or float or a “unit”ed meter and also a cv::Point or Vector to create the desired affine Point+Vector types mentioned above with the proper semantics.

However, I have not yet written this library and will leave this, for now, as the proverbial though challenging “exercise to the reader”. It does seem to require a powerful strong-type facility that can also transparently handle both primitive 1D types, unit types and custom user defined types (the libraries mentioned above are mostly geared towards 1D primitive types).

If you do come up with such a generic library facility - do let me know and I will link to it here.

Acknowledgements

Björn Fahller reviewed this post and made excellent suggestions and comments. Thank you Björn!

This post was also inspired and encouraged by multiple discussions on the C++ Slack.

Corrections and inaccuracies were kindly pointed out by: @ubsanitizer, @Matt

❤️

I ❤ feedback, so if you found this post interesting or you have more thoughts on this subject, please leave a message in the comments, Twitter or Reddit. If you know of generic solutions to this fascinating structure, please DO let me know and follow me on Twitter for more updates.

References

- The presentation Affine Geometry by Jehee Lee (PDF ver.) had the least amount of math jargon and is the basis for many of the Definitions I presented here.

- In an answer to my question Affine Spaces and Type Theory the answerer suggests a C# CRTP solution as a generic affine utility.

- These notes provided good explanations of affine combinations and barycentric coordinates.

- Eli Bendersky has an approachable blog post about Affine Transformations.

- The indefatigable Norman Wildberger presents Affine Geometry in the video AlgCalcOne: Novel Algebraic Operations for Affine Geometry

- Björn Fahller’s ACCU 2018 talk Type safe C++ – LOL! :-) gives an overview of the strong type libraries mentioned above and gives an explicit example of strong types with affine space semantics.

- Mathematically oriented references include Wikipedia, MathWorld and nLab Category Theory Wiki. This book/course chapter Basics of Affine Geometry goes into a lot of the mathy details.

- In A mathematical formalisation of dimensional analysis Terry Tao discusses the related subject of unit types and dimension analysis from a mathematical perspective.

Footnotes

-

In C++ (and C) the correct “type” is in fact

std::ptrdiff_twhich on some platforms may not be anint. To be totally pedantic: “std::ptrdiff_tis the signed integer type of the result of subtracting two pointers.” The actual type is implementation-defined. ↩ -

For the pedantic, yes, only pointers to elements of the same array (including the pointer one past the end of the array) may be subtracted from each other, otherwise the behavior is undefined. ↩

-

I am quietly ignoring any undefined behavior due to signed overflow. ↩

-

At least for the non-

InputIteratorcases. ↩